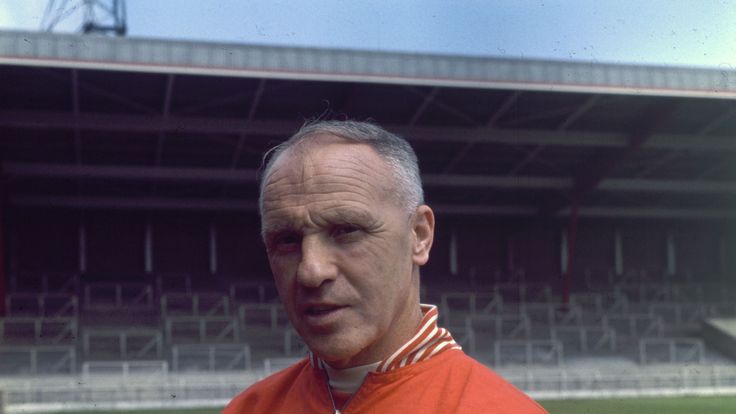

Alex Dunn caught up with Red or Dead author David Peace to discuss his literary love letter to Bill Shankly.

David Peace's latest novel

Red or Dead, which weighs in at over 700 pages and 250,000 words, has at once been described as 'a masterpiece' and 'Rain Man with a Rothmans'. Following on from his depiction of Brian Clough's tumultuous 44-day spell as Leeds United manager in

The Damned United, the British author has trained his sights on Bill Shankly's tenure as Liverpool boss from 1959 to his shock resignation in 1974. The trials and tribulations of retirement inform the second half of a book that, for this reader, more than achieves its primary intention of getting to the heart of who Bill Shankly was and what he represented.

As with any Peace novel, his visceral and repetitive prose style has been much commented upon but it is more his perception of a man he spent more than a year researching that we were keener to discuss on being granted an audience with the Yorkshireman on publication, just before he returned to his adopted home in Japan.

I never thought it would be a David Peace novel that restored a little faith in humanity. You've described Bill Shankly as a 'Secular Saint' - were you surprised over the course of writing and researching the book by just how much affection you discovered you had for him?

I'm glad you say that, actually. That was certainly one of the intentions when writing it. After the kinds of books that I've done, which have been explorations of the more, shall we say, darker sides of life, I wanted to do something that wasn't just a criticism but something that offered an alternative.

In the past you've written about individuals tearing communities apart, Shankly was someone who drew them together. Did you enjoy the process of writing about a saint rather than sinner?

Absolutely. One of the reasons that the book is so long is that it was hard to let go, really. Researching and reading about a man like Bill Shankly was an absolute pleasure, and likewise to be in a position now to talk about him with you is an absolute pleasure. That's the effect he had on people and has certainly had on me.

How much as a Huddersfield Town fan was he already part of your consciousness?

He was to some degree. Huddersfield supporters will always say, 'if only the board had given Shankly the money for (Ian) St. John and (Ron) Yeats, Huddersfield would be where Liverpool are now' and vice-versa. There was that element of it with my father and grandfather talking about him but he resigned in 1974, which was where my footballing memories begin with Brian Clough going to Leeds United. He was never an active manager from when I was seven onwards. I do, though, remember the 1965 FA Cup final - Liverpool versus Leeds - very clearly. That's one of the things that drew me to him - trying to learn more about the story. It's very different than if you'd grown up a Liverpool supporter or on Merseyside, as you're very much aware of his legacy. Outside of the city, though, you know the anecdotes and the legend but not the details of the man himself.

"Liverpool was made for me and I was made for Liverpool," is an oft-quoted Shankly line. It was clearly a special relationship he enjoyed with Liverpool and its people but could he have replicated his success elsewhere?

Huddersfield Town supporters would certainly say yes. I do think that there is something particular and unique about what he did at Liverpool, though, mainly because of the relationship he had with the supporters. One of the reasons he left Huddersfield, his family were very happy there, was because he knew what kind of people they were on Merseyside. They knew they had fervour and a passion that he said himself he only ever really found in Glasgow. I think that enabled him to create this incredible bond with supporters, who in turn became the twelfth man to raise the team. I think Newcastle is another region where he might have built a similar relationship and had real success.

I found the stories about him regularly inviting supporters into his own home pretty remarkable. How important was it that you made him a three-dimensional character that went beyond the surface of his witticisms?

It was the main motivation. To paint the portrait of the man and go beyond the quips and famous lines - or to put them back into the context of the hard work - was paramount. Number one I wanted to get across the sacrifices he'd made and struggles he'd gone through. Number two, and this goes into the repetitions in the book and domestic scenes, he saw himself as an ordinary man, and I wanted to reflect that. He was an ordinary man but one who did extraordinary things. In this respect it was important to show him doing ordinary things. Washing the car, doing the dishes, scrubbing the floor, laying the breakfast table, whilst at the same time he's transforming the lives of the people around him.

Shankly created a team very much in his own image - a working class team for working class people. What was it about him that made both players and fans buy into a vision that took Liverpool from the Second Division to League champions?

It's not an easy question to answer, it took me 720 pages! To me it was the socialism that was informed by the place he grew up in, Glenbuck. It was a mining community where in order to triumph over the poverty and the terrible conditions of the work, the only way that could be achieved was by working together. People helped one another and that's where Shankly's vision of socialism came from. He took that on and it informed everything he did; both on and off the pitch. He treated everybody equally, thought the best of people and endeavoured to make those around him happy. He thought of himself as the exact equal to supporters of the club - no better or worse. People then looked at that and thought, 'well you're the same as us', and it was in that way like a marriage.

That period in football was remarkable in that Britain's top managers, Matt Busby, Jock Stein, Bill Shankly and after that Brian Clough all held cast-iron socialist beliefs. From a personal perspective do you see that period as a halcyon time?

Don Revie as well. You've got to be careful not to look on that period with rose-tinted glasses but what those men represent to me epitomises the 1945 Labour government. These men have all come from extremely poor backgrounds, from communities involved with very, very difficult industries. That then has informed them and the beliefs inherent in these communities has been carried over into their working lives. In a similar way the trade union movement, and the Labour government of that period, created the welfare state, imposed radical changes to healthcare and pensions, the education system and nationalisation of key industries. It's hard not to see that as a halcyon time. It was the only time that the working class were able to truly get what they deserved out of society after putting into it. Obviously it's a time that I wish would come again.

There's no greater example of him putting principles into practise than paying his team that won the FA Cup in 1965 the same wage...

Exactly. What's really interesting is that in retirement, in the chapter 'We must get back to sanity', which is a line of his, he's talking about the ridiculous fees paid out in transfers and wages. Even then he was railing against players having flash cars without having ever won a medal. It's interesting that this all comes in and becomes such an issue around 1979, which coincides with the Thatcher General Election victory. It's this increasingly 'every man for himself attitude' that pervades society in the years after Shankly's death. That's the message, the propaganda of the government of time, so we shouldn't be surprised. There's no looking out for anyone else, there is no society, just the individual.

The problems he foresaw, the laments over how much players are getting paid and the power they're starting to yield, are the exact issues that rankle still today. Do you think football is out of control in this respect?

What I would say is that it's really easy to blame footballers, it's really easy to bang on about Suarez. Luis Suarez is the individual and that's what our society does, it turns everything onto the individual. It's not Suarez's fault, it's not football that's out of control, it's society that is out of control. Since about '79 onwards this has just got more and more extreme. The propaganda, and it's not so much the government as advertising, perpetuates the idea of everyone being out for themselves. Football is out of control only to the extent society is out of control.

You've freely admitted it's a hagiography, can anyone really be as virtuous as Shankly?

I have said it's a hagiography because to me he is a saint. He did have his flaws, though. One of his great weaknesses was that he found it very difficult to deal with players that were injured and players who were coming to the end of their time. In a way this was borne out of one of his qualities, though, in that it was because he was so devoted and loyal to them, as they were to him, that when they were injured he found it very difficult. Like a lot of us it's hard to know what to say or do in these type of tricky situations. Sometimes he handled it badly. I think it had something to do with the greater battle he had with time, mortality and time running out.

You've said novels are as much about the time they're written as the time they're written about. In what ways do you see the novel relating to today's issues?

In writing the book in 2011-2012 I'm drawn to the bits that relate to today. This is where the influence of having a present takes effect. I picked out some of the things that he said which in some respect still have a relevance to what's happening now. I was back living here from 2009 to 2011 (Peace moved to Japan in 1994 and is back living there now) and I think the book is really about that as anything else, really. Going back to what I've been touching on, when I came back to England after living in Japan it made me appreciate the great quality of education and healthcare in this country and yet at the same it felt like it was being chipped away at, privatised, split up and palmed off. I just thought I'm not alone here in thinking 'what's going on?', where is the great battle to save the welfare state? The privatisation of the gas and electric companies meant that my mum and dad spent the entire winter worrying about how they're going to pay for their heating and that for me is that legacy of Thatcher. That's her legacy right there, that the old people of this country can't afford to heat their own houses.

Would Shankly then have been able to manage in a society almost diametrically opposed to his own belief system?

It's a fascinating question but obviously it's pure speculation and impossible to answer. The only thing I would say is that you have to remember that when he went to Liverpool he revolutionised what went on at that club. He was the first ever manager at Liverpool Football Club to actually pick the team. He was the first ever manager who really dictated, along with Paisley, Fagan and Reuben (Bennett), the training schedule. Clubs were still run by directors and owned by men with money. The nationalities may have changed in the league today and the amounts that are paid has escalated, but there's never been a time in football where the people have owned the team. In a way, it was the same as it is now. Going back to Stein, Busby and Shankly they were coming from backgrounds that thankfully most of us, not all of us, don't come from in terms of the poverty. If you look at the odds they triumphed over, I think a man of such determination and intelligence of Shankly could adapt and manage today. The problem now is that we are conditioned day in and day out in accepting things, accepting that we can't change things. Bill Shankly never believed that, he was a radical and revolutionary man. He'd have never taken that and would have tried to change things.

How important was it for you to share Shankly's philosophies - both sporting and social - with a younger generation who know only the myth of the man?

That was a strong motivating point for me, to be honest. I was thinking about my kids who are 16 and 13. When I was growing up, and I'm 46 now, whether you chose to embrace or reject socialism, it was always there as a choice. You knew what it was and at least you had the choice. For my kids, if they didn't live with me, I don't think they'd have even heard of the word. What I hope the book might do for a younger generation is say, 'look, things weren't always like this. There was once this man who lived his life in this way and inspired a lot of people. He was informed by socialism and it might be worth having a bit of a think about it and what it represents'. As grand as that ambition sounds, I just feel it is something that has just disappeared from any kind of debate.

'Repetition, repetition, repetition' starts the novel. It's a mantra you've embraced in your writing. In this respect with regards how Shankly liked to work, in a similar vein, do you think you were an ideal fit?

Perhaps. The repetition of the silence was really influenced by making the portrait of him as true to the spirit of him as a man. I recognise things in his working methods that I saw in myself. Maybe this is one of the reasons why I could relate to him.

You borrowed the tapes of John Roberts, who ghostwrote Shankly's autobiography, so literally had him in the room with you while you were writing. As a reader you get a similar sense of intimacy. Are you happy you've caught the essence of the man?

It would be hard for me to say. It'd be terribly smug for me to say 'I'm really happy with the job I've done' but what I would say is that when the Shankly family or a player like Willie Stevenson has said, 'you've caught 85 per cent of the Shankly I knew' it's for me a real compliment.

So much has been made about the book's style, are you surprised it's been the singular aspect most commented on?

To be honest with you, I don't know about reviews. I take more heed of what people say on Amazon than in the newspapers. I don't sit studying the reviews on Amazon by the way, but my daughter kindly tells me whenever people have given me one-star reviews. What I find a bit frustrating is when people say, 'you're doing it to be pretentious or to shock us'. You might not like it but that's certainly never been the intention. I'm not saying I succeeded but it was never a literary show-off trick. I thought this was the best way to show the fabric of the man and the culture of the time. It was always an attempt to paint a portrait of a man with all these repetitions and struggles. As much as I could I wanted the reader to experience his living experience, and I'm not saying I achieved that, but it was never an intellectual exercise on my part.

Liverpool have always been heavily criticised for the manner in which they treated Shankly in retirement, but do you have any sympathy in that they were put in a tough position as they needed to give Bob Paisley space to breathe and manage in his own way?

I tried to be even handed with this but some Liverpool supporters have said I've been too kind on the club in this respect. They did beg him to stay, they did offer him money, they did offer him a directorship. There was all that but of course I think he failed to really understand what retirement would mean and never appreciated what this sense of exclusion would mean for him. There was a fair degree of misunderstanding and pride on both sides.

Whilst there is genuine pathos in the second half of the book, overall I found it an uplifting read. What is your take on his life after retirement?

Again, what I keep coming back to, is that people say Bill Shankly spent his years after Liverpool with a broken heart, King Lear in the wilderness, but I don't think it was ever that simple. I think his whole relationship with the supporters meant he always knew how revered and appreciated he was by the fans of Liverpool Football Club. I don't think he ever lost his love of the game, whether that be playing with the kids on his street or non-league football. He just had this tremendous love of the game and a tremendous love of life. Even in his darkest days I think he retained this. It's 720 pages but it could have been so much longer as he genuinely made such a huge impression on so many peoples' lives. Primarily because he had the time for them.

Do you think football clubs are still a source of social good?

A lot of clubs do try, some are more successful than others but the potential is there certainly. With the collapse of the trade unions football is one of the very few places where people come together. Admittedly, usually they're not coming together perhaps in the spirit of friendship and community but there is that potential there.

You wrote the Red Riding trilogy, the third of your Tokyo-based novels is on the way, can we expect a hat-trick of football books? Are there any living managers, hypothetically, you see as interesting subject matter?

I think you might, yeah. Trilogies are always good. No, I won't be elaborating more at this stage! There's the potential there for so many clubs and so many managers. I'm surprised there haven't been more football novels written. When I began the

Damned United, Brian Clough was still living, so, yes, I would (write about a living manager). Gordon Burn has always been a big influence and

Born Yesterday, where he wrote a novel using living contemporary people, is something that's really interesting to me.